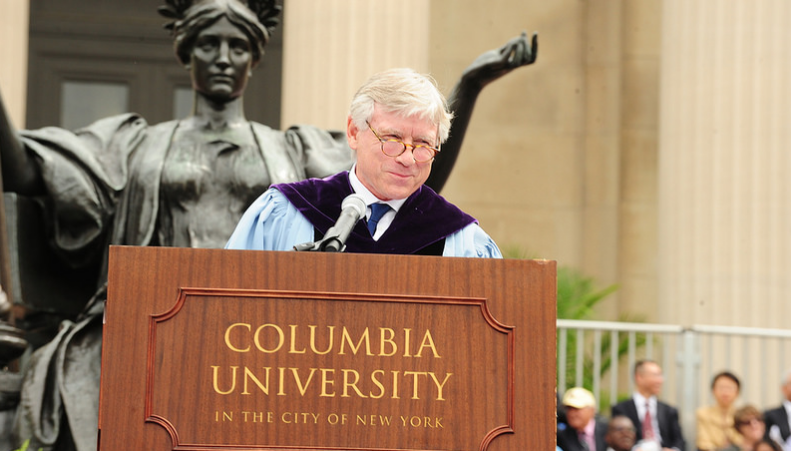

2016 Commencement Address

May 18, 2016

On behalf of the Trustees and the faculty of Columbia University, it is my very great pleasure and honor to welcome all of you to this ceremony to celebrate the graduation of the Class of 2016. It is our tradition to gather in this magnificent setting, surrounding Alma Mater, to affirm the knowledge acquired by our extraordinary students and to recognize their remarkable achievements. You are now intellectually and loyally connected to all those who have been here before you over the past 262 years and to all those who will come for centuries ahead. You represent sixteen different schools, along with our affiliate institutions of Teachers College and Barnard. And each of you here today is forevermore linked to one another through a scholarly bond that is now forged in this very special place at this precise point in time.

While this occasion is about you, there are also a few people here today whom you’ll never be able to thank enough. I can assure you that nothing focuses the mind like the successes and disappointments of one’s own children. And, as much as we, your faculty, feel deep affection for you, nothing can compare to the pure adoration of your parents and families. Please, take this opportunity to thank them.

Though there is certainly a reassuring and pleasing familiarity in the rituals and trappings of this grand ceremony, it is also the case that each Commencement is distinct—informed by its specific time and the unique features of the world graduates will find upon leaving Columbia. This year, it is fair to say, we gather at a moment when several of the tectonic forces that for decades have shaped modern life for billions of people around the world appear to be shifting, and perhaps abruptly. It is these potential human, societal earthquakes, happening or potentially about to happen, that I want to speak about this morning.

For those who care about freedom of mind, of speech, and of expression; for those who believe the best life is one lived amidst a broad array of beliefs and ideas that make possible a collective quest for human truth; and for those who seek to develop their intellectual capacities for any number of important reasons—to deploy reason for good ends, to appreciate the complexity of life, to know as much as possible what humans have learned over the millennia, to master the art of conversation and civil discussion, to expand tolerance in a world that can never be as we would want it to be—for those who care about these things, this is a disconcerting time.

The continuing appeal of intolerance and the persistent attraction of authoritarian rule are sobering facts of contemporary life. When this mentality prevails in countries with histories of dictatorship, that’s one thing. Deplorable as it is, we at least know what we’re dealing with. But when it takes hold in established democracies—as it is right now in several democratic nations, perhaps even including our own—we are, by turns, unnerved, mystified, and even shocked. At this moment and in this place, as we come together to celebrate thousands of graduates dedicated to the quest for learning and wisdom—how can we escape asking where the world is truly headed?

The most obvious causes of these trends toward so-called illiberal democracies—a term reflecting democracies being self-destructive—are often said to be tied to the defining realities of modern society: an unstable and rapidly shifting balance of power among nations; globalization of markets, of communications, and of populations; and differential consequences across and within society, enhancing the welfare of some, but undermining the employment, incomes and expectations of others, who are now expressing their frustrations and angers in public forums and at the ballot box. To be sure, these are all important contributors to the state in which we find ourselves.

But what if these warning signals are the product of something still deeper and more profound—a consequence of the changed structure of public thought and discussion itself? What if the very foundation of democracy—a commitment to hearing every voice and viewpoint, and a belief that from the resulting clash of ideas the truth will prevail—what if that core idea is not only no longer valid but actually, and ironically, abetting the abandonment of democracy? The arguments for this disturbing perspective, which we can expect to hear with increasing frequency, are not without force: online social platforms have made it easier for people to insulate themselves from opposing views by providing an inexhaustible supply of opinions corroborating what they already believe. This process of steady reinforcement makes us self-righteous, less tolerant and, eventually, angry when we are confronted by contrary positions.

There is also the technology-enabled habit of skimming news for headlines, which thins out our knowledge and perniciously makes us superficial without realizing we are. But even worse, we are losing the basic norms of civilized behavior. Falsehoods are circulated without correction or consequence, individual privacy is disregarded, and bullying and cruelty towards others seems normal.

These criticisms—taken together and in the context of the rise of authoritarian political movements, where extremes seem to be crowding out the moderate and sensible, the serious and intelligent—cast doubt on our entire system of public discussion. For the moment, it appears that democracy is falling victim to a downward spiral of anemic debate providing fertile soil for intolerance and repression, which, in turn, does further damage to meaningful public discourse, ultimately leading to its collapse.

As powerful as this critique is, there are strong reasons why it is not yet time to despair.

First, it is important to understand that every new communication technology—beginning with the printing press, in the 15th century, and then, in the last century, radio, television and movies—has been greeted not with enthusiasm and protection but with guarded fear and regulation. Virtually all the criticisms being leveled at the Internet are echoes of forecasts of great harm that were made when these earlier technologies suddenly appeared on the scene. There were worries of moral degradation, sedition, opportunities for propaganda and manipulation of public opinion, and all of these fears led to regulations that subsequently were found to have been excessive. Of course, the fact that these fears proved to be unfounded before does not necessarily mean they are false now, in this potentially different context; nonetheless, our history and this consistent overestimation of the harms of new methods of communication, at the very least, ought to make us hesitate and think very carefully before acting to impede the development of still newer innovations and the discussions they facilitate.

Second, the principle of freedom of speech has become perhaps the most widely-embraced civic value in our nation, existing beyond partisanship, precisely because the courts, and then the public, infused this constitutional guarantee with a sophisticated appreciation of human nature. There is nothing naïve about America’s conception of this basic right. We champion freedom of expression while recognizing that, for human beings, intolerance is often the very first impulse, but we choose to push ourselves to a higher ideal of what life can be.

Almost one hundred years ago, Oliver Wendell Holmes set forth the first modern articulation of the world we have come to know. To a nation gripped by widespread intolerance and censorship arising from the fears of World War I and the new ideology of Communism, Holmes advocated for the first time the metaphor of the marketplace of ideas as preferable to our proclivities to be intolerant. With open recognition of the troubling side of human behavior, he said:

“Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition.”

Holmes understood very clearly that free speech is counter-intuitive—an insight that applies to all learning, generally. It takes enormous concentration of effort and dedication to learn, to become educated, to achieve what you are being recognized for today. No one takes exams or writes term papers because that’s their first choice about how they’d like to spend their time. We create contexts, the First Amendment and universities being two of the most important, in which we hope to overcome our impulses.

So, when we look at what is happening in today’s political environment, we should not despair and wring our hands, as if we’re confronting something wholly new and unprecedented. As bad as you might think things are right now, every generation has gone through versions of this—the intolerance around World War I I’ve just mentioned and the McCarthy era being two examples—and struggled to come through to the other side. Perhaps life online more greatly enables our worst instincts, but before amending our principles, I’d wait for greater proof of that view. This is just the most recent test, which we must work through, just as it is certain future generations sitting here will have theirs.

And this brings me to the third, and last, point. There is an available remedy, even if it is an uncertain cure. For most of the past century, the progress on openness has been bound to the belief that persecuting dangerous ideas comes at too great a cost and turns us into people we don’t want to be; all views, therefore, must be given their chance, no matter what we think of them. To be sure, it is a risky enterprise. We choose to live in a wilderness of ideas where we have to fend for ourselves.

The remedy starts with engagement. You cannot stand back and then be shocked at the consequences. You have to expect and prepare for exactly what’s happening now. Think of it this way: You’ve been drafted and there’s no avoiding it. It does little good to stand on the sidelines and complain about the state of public debate. But it’s also more than just joining the fray and advocating your viewpoint.

What’s necessary—but very hard—is to make your own contribution to engaging in genuine public discourse in a way that reflects the deeper values of a tolerant and educated mind. Just as we now say that every nation has a Responsibility to Protect its citizens, the principle of free speech says you have a Responsibility to Participate, to protect this core value of our democratic society by exhibiting the qualities of mind and attitude that make the whole enterprise sustainable. This is how freedom of expression and robust debate survive and thrive over time, the only way really.

There is and will be a role for you. I can assure you of one true fact about your lives. There will come a time, probably several, when you will sense that around you the natural impulse to intolerance is rising and that you are in a situation to say or do something against it. It is a certainty that the pressure on you to succumb or go along will be nearly overwhelming. The “logical” nature of intolerance, as Holmes, put it, makes it also insidious. It may be on a school board, a social organization, or an election—maybe too, you will run for President of the United States. Our hope is that you will draw strength from your wisdom and experiences gained here at Columbia and that you will stand for what we stand for.

And there is a role for Columbia. We can and should be more engaged than we are with the problems of the world, in the way that only one of the greatest universities in the world can. There is an urgency about the problems we are facing, as a nation and as a world, and there are not many who bring what we do to addressing them. Of course the heart of our enterprise is and must remain fundamental research and advancement of knowledge. But no university can survive, and no society can flourish, unless it aligns itself with the needs of the people. We are justifiably proud of the hundreds of engagements we have with the real world outside these walls. But we can and should do much more, and I hope in the years ahead you will take added pride in the things we have and will accomplish in this domain.

Here, then, is my argument: The rise of the illiberal democracy is just the latest phase of a permanent risk, borne of our natures and built into the premises of the principle of freedom of speech, the search for truth, and the quest for a good life. Better to take it as a given, prepare and be ready for it when it comes, and to deploy the only weapons we have: wisdom about human nature, our impulses and our ideals for ourselves, and the institutions we have structured in response to it. We must draw from within us, as hard as it may be to do so, the values that we strive to live by. This is and will forever remain a vital part of this great university’s mission, and one I ask you to embrace as you leave this campus and go out into the world.

Congratulations to the class of 2016.