In 2003, when I proposed in my inaugural address that space was a critical element in the future of Columbia University and that I believed Columbia’s future should be within our home community of West Harlem, I knew several things: I knew that Columbia’s intellectual ambitions could not be achieved without major new physical space. I knew that, ever since competing visions of urban planning collided in the heated controversy over Columbia’s proposed Morning- side Park gym in the late 1960s, Columbia’s capacity to fulfill the ever-increasing potential of a great American research university had been physically limited. I knew that a piecemeal, building-by-building approach to growth in our community would take too long and probably ultimately fail; and that a larger vision—a smart urban plan for an entire new campus—held the greater likelihood of success.

I knew that Columbia had to embrace Harlem and upper Manhattan as its home and neighbors, with all the longtime challenges and special magic that coexist in this iconic community. I knew that the building of a new campus in the industrial area known as Manhattanville had to be seized as a moment to project the intellectual excitement of new knowledge, including the remarkable creativity in art and culture that we are encountering in this new century. And I knew that the physical buildings and spaces had to be approached with the same expectation of creativity that we would bring to the academic work taking place in that new campus. At the same time, I believed strongly that we had to create a new and different kind of academic space that would both serve our own mission and be a welcome addition to our city. What I didn’t know was how daunting the challenge of achieving this vision would be. Fortunately, countless numbers of supremely talented people (many mentioned in or part of this volume), within the university and outside, including our elected and appointed officials dedicated a good portion of their lives to bringing these ideas and values to reality.

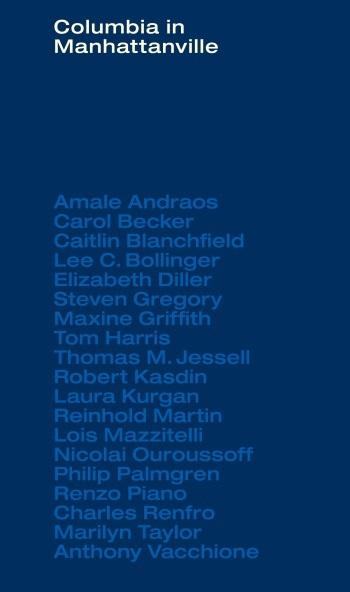

Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation has been a vital partner in the Manhattanville project. Mark Wigley and now Amale Andraos, as deans, have been friends, colleagues, and advisors in the long process. The school has played many roles, most notably as a kind of conscience reminding us of the need to keep physical planning and design in close alignment with the intellectual and human ambitions inherent in something of this scale. Now it is time for self-refl and there is no better way to do that than through a work like this book. I am, therefore, extremely grateful for and admiring of the school, and Amale, for undertaking this project. We are only at the beginning of the journey, and this book will play a signifi ant role in shaping how we should look ahead.