2018 Commencement Address

Image Carousel with 8 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

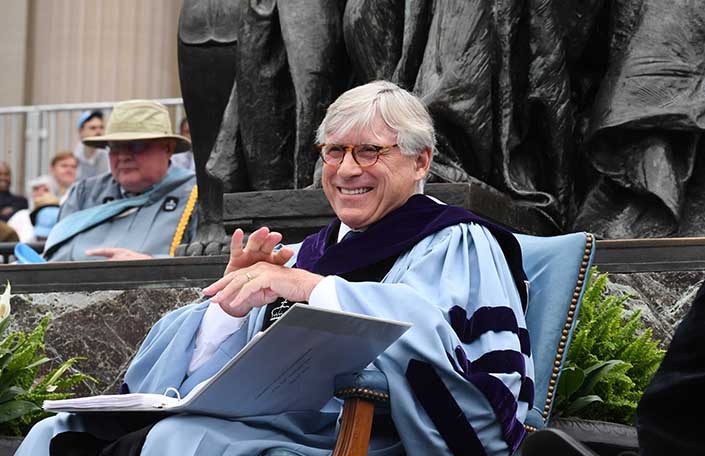

Slide 1: Photo Credit Chris Taggart

-

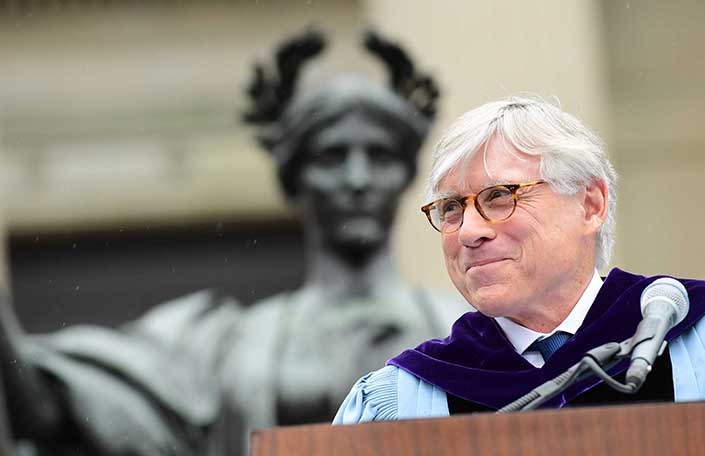

Slide 2: Photo credit Eileen Barroso

-

Slide 3: Photo credit Eileen Barroso

-

Slide 4: Photo credit Chris Taggart

-

Slide 5: Photo credit Eileen Barroso

-

Slide 6: Photo credit Chris Taggart

-

Slide 7: Photo credit Eileen Barroso

-

Slide 8: Photo credit Chris Taggart

Photo Credit Chris Taggart

Photo credit Eileen Barroso

Photo credit Eileen Barroso

Photo credit Chris Taggart

Photo credit Eileen Barroso

Photo credit Chris Taggart

Photo credit Eileen Barroso

Photo credit Chris Taggart

May 16, 2018

On behalf of our Trustees, our faculty, our distinguished alumni, our families, and our many friends of Columbia University, it is my very great pleasure to welcome you all, whether you are among those gathered here on our Morningside campus or among the tens of thousands joining us virtually. Today, we continue our 264-year tradition of celebrating the significant achievements of our graduating students and of placing them in the prestigious legacy built by others before them. The journey from a Columbia student to a member of our alumni community is a rite of passage—given only to those with the loyal commitment to open-mindedness, to intellectual curiosity, and to the pursuit of greatness. Representing sixteen different schools, along with our affiliate institutions of Teachers College and Barnard, you, the class of 2018, are bound together by the responsibility of the knowledge you have acquired in this special place, in this moment in time, and by the shared responsibility to use the power of that knowledge to shape the world.

And while this is an occasion about you, there are many people whom you’ll never be able to thank enough. As much as we, your faculty, feel deep, deep affection for you, nothing can compare to the pure adoration of your parents and families. Please, take this opportunity to thank them.

There is a most reassuring and pleasing familiarity in the rituals and trappings of this grand ceremony, but it is also the case that each Commencement is distinct—and one way in which it is distinct is because it is informed and affected by the unique features of the world that the graduates find upon leaving Columbia. I have to say I think the world you and we are experiencing now is deeply troubled. That being so, I have felt it important this morning to talk about the idea of a core in life, a center, around which our lives must evolve. Naturally, I want to begin here at home and speak about our own undergraduate Core Curriculum, which several thousands of you have experienced first-hand in some form.

My thesis for this morning has to do with the idea that a core is a set of values and intellectual habits of mind that are essential to the health and well-being of any society, any institution, and any individual. When they weaken, they must be shored up; when they are challenged, they must be defended.

Many universities claim to have a core curriculum, but few even come close. Usually, it is only an assemblage of courses already created that are then deemed a “core,” and every student can select from the list. The first thing, therefore, that distinguishes the Columbia Core Curriculum is that the content has been specifically composed, primarily as a set of texts and works of art, that must be read and engaged. There are real choices made about content, which of course makes it—I would say absolutely appropriately—always subject to disagreement about what should be in and what out. But the truly distinguishing characteristics of the Columbia Core go well beyond this.

In its ideal form, the Core is taught universally, to all students, in small discussion sections that provide a distinctive opportunity for students to engage with both teachers and one another in joint exploration and discovery. Finally, there is the stunning ambition of taking that engagement with what are generally classic works and thinking about their meaning and implications in the context of contemporary issues. So, immediate and serious engagement with original texts and works, in small discussion groups across each class, under the guidance of a professor not necessarily an expert, with an aim of relating everything to life as we know it now.

Why is this idea so powerful? One key element is somewhat counter-intuitive. It is just a fact of our intellect that to experience a sense of wonder and amazement about what human civilization has produced you have to get closer and closer to it. On first glance, most great achievements seem ordinary, obvious, or impenetrable. Sometimes, as is true with Shakespeare, you can enjoy a play even though you know little or nothing of the underlying symbols, imaginative use of words, or the profound ideas at work. But usually this is not the case.

My favorite observation of this fact comes from Virginia Woolf’s diary where she says: “I read Shakespeare directly I have finished writing. When my mind is agape and red-hot. Then it is astonishing. I never yet knew how amazing his stretch and speed and word coining power is, until I felt it utterly outpace and outrace my own, things I could not in my wildest tumult and utmost press of mind imagine.” The closer Woolf feels to working alongside Shakespeare, the more intense her appreciation grows. Thus, it is a gift to be young and to be introduced to genius, in a way that will make it forever possible over a lifetime to return and deepen that capacity to experience more poignantly the mysteries of genius.

But there are things to note of far greater significance here. It would be wrong to think of the Core as merely offering a kind of “finishing school” experience in the appreciation of masterpieces. In truth, all of the content is about the most fundamental and highly contested issues of life. How should power in a society or among individuals be allocated and exercised? Should there be rule by elites, by religious leaders, by workers, by superior individuals, by brute force? What is a just society, and how should benefits be distributed? Equally, by merit (what is merit?), by the best form of collective meaning? What is morality, ethics? Why should we impose any limits on our wants and desires in the interests of others? Do we have free choice? Can we ever be “objective,” or are we always a captive to our own preferences? What can we know, of ourselves and the world?

These and a host of others comprise the profound puzzles of existence, and there are radically different ways of thinking about them, and, most importantly, our lives will play out very differently depending on how we answer them, as we, in fact, must. Therefore, to be submersed in these questions is to feel both the exhilaration of widening our grasp of what life offers and the consternation and even fear that accompanies the dissolution of what we theretofore have taken for granted and cannot any longer. The key point is that the Core brings us closer into fundamental debates and also creates a habit of mind that is more open, more comfortable with conflict and uncertainties, and—here’s the bet—more tolerant of the vast multiplicity of ideas that the human intellect yields.

Now, these two reasons—the fundamental questions raised and the habits of mind instilled—are why the Core radiates outward through the entire University represented here today, and from there to society at large. For there is no field or discipline, or area of life, that ever escapes these issues or does not call upon the intellectual character nurtured in that core environment. So, the Core is to the University what the University—and the best of higher education—is to the society, namely part of its core.

Particularly at moments of transition and upheaval, society must turn to fundamental values, among them a commitment to freedom of thought and expression, dedication to tolerance and reason, an insistence on the primacy of facts, respect for diversity and differing points of view, and a determination to pursue these values with the utmost integrity and courage. American universities, long the envy of the world, have functioned as a wellspring of these values for the nation, and Columbia’s Core Curriculum is the exemplar of this essential societal resource.

The Core Curriculum was first conceived and designed by Columbia College faculty and deans 100 years ago as a course on “war issues” for the U.S. Army in 1917-1918. In 1919, it first became a college course here on campus, known as “Contemporary Civilization.” It was born out of the sense of a world in disarray—and so much like our world today. A World War with enormous loss of life and casualties, followed upon some decades of increasing global integration. A conflict that, in the horrific new weapons it unleashed for the first time, and in the inhumane treatment it inflicted on soldiers and civilians alike, made clear the need for a new set of global norms to govern the conduct of nations. A world coming apart, as empires disintegrated, nation states reconfigured, and powerful new ideas about the development of nations and societies proliferated. In the United States, fears about the security of the country mounted. The focus, as always, was directed unfairly on “foreigners” and “aliens.” Of special concern were the Russians, where the new revolution was believed to have subversive intentions here.

In the ensuing “Red Scare,” most states enacted laws prohibiting the display of a “red flag” with seditious intent, advocacy of “criminal syndicalism” and “anarchy,” while the federal government prosecuted thousands of citizens and foreigners under the Espionage Acts of 1917 and 1918, including a leading candidate for President of the United States. Meanwhile, there was growing concern about the press debasing public debate. Some years earlier, Louis Brandeis had written in a famous article about how the press was becoming fixated on “triviality” and “gossip,” in disregard of personal privacy which was destroying “robustness of thought” and diverting “brains capable of other things.” Now these concerns were redoubled with the emergence of a new communications technology known as broadcasting. In all this sense of mounting chaos and closed-mindedness, wise people thought things had to be done to open minds. The Core Curriculum was thus invented.

Close to home, also invented in this churning, contradictory American moment of a century ago were the Pulitzer Prizes, which grace this University to this day and which we will hand out later this month in that iconic building behind me. So was our School of Journalism, both of which were created by the publisher Joseph Pulitzer, who believed they were needed because “An able, disinterested, public-spirited press, with trained intelligence to know the right and courage to do it, can preserve that public virtue without which popular government is a sham and a mockery.”

And so, too, was the First Amendment invented at this point. Even though it had been part of the Bill of Rights since 1791, it wasn’t until 1919 that the Supreme Court first decided a case about the meaning of “the freedom of speech or of the press.” The Court, the Pulitzer Prizes, the Core Curriculum—all these were created as a response to the rabid intolerance that was spreading across the country.

From the outset, it was manifest that the new First Amendment was not only about limiting censorship but, more importantly, about articulating in this profound context the basic intellectual character, the qualities of mind, of the nation. In a series of seminal opinions by Holmes and Brandeis especially, they defined free speech in terms of overcoming our natural impulses to intolerance and persecution, of reflecting on life and realizing how “time has upset many fighting faiths” and asking that we put our trust in the collective effort to discover the truth, and because truth is everything and “the only ground upon which [our] wishes safely can be carried out,” and saying further that the “freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth,” that “discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine,” that we are “not cowards” and that the “function of speech [is] to free [us] from the bondage of irrational fears.”

All these and many other efforts were expended to create and shore up the core of our social life, at a time that seemed desperately in need of reconnecting ourselves to some ideals. In every case I’ve mentioned, they took root.

They grew and prospered and became part of a book that holds the essence of a good life. Of course, any core must live in the real world, and the real world will always be riven with conflict, bad temperaments, ruthless self-interest, tactics to seize power, and manifesting the worst of human instincts. We are not naïve. But, without a core, alive and well, the risk of drifting off the deep end of existence is alarmingly high.

The First Amendment offers a striking example. As it has evolved, we know that the choice has been made that even terrible ideas receive protection. This has a purpose. We often say in life that we need to learn to disagree without being disagreeable. That’s, of course, true. But we also have to learn to disagree with really disagreeable people who have not learned the first lesson. Unfortunately, there are many of those, and mastering that capacity for that reality is actually a very important element of living well in a democracy. But for us to learn that we need to feel confident there is a core most of us share that rejects these bad ideas. Every single First Amendment case that protects extremist or outrageous speech contains an explicit statement reaffirming our core beliefs and rejecting the terrible ideas, even while protecting them. It’s all part of a package that lets us learn something important (tolerance) while feeling secure in the existence of a core in a society—which is one major reason why the statement along the lines of “there are good people on both sides” about the Charlottesville events was so harmful and undermining of what we have built up.

This brings us to today. I don’t think I need to belabor the point that it feels like we are in a very similar situation now to where we were a century ago. The problems are obvious, and parallel, to any sensible observer. The real question is what we will do about these problems.

Certainly, we can learn from what we have experienced and from knowing something of its origins and other similar efforts. There are now 27 amendments to the U.S. Constitution, and we could propose a 28th, adding to the requirements of being a “natural born Citizen” and at least 35 years old, that “No person . . . shall be eligible to the Office of the President” who has not taken the Core Curriculum and received a passing grade.”

But the obvious and serious point is that we must continue to do our very best to make the institutions we are part of, like Columbia, the standard bearers of the bedrock of that “core” of life that must call us back from the brink. That we are deeply committed to doing in every way we can, particularly in this moment, when—in this country and in our increasingly interconnected world—the ability to define a fundamental set of truths and values, and to resolve big issues, feels more and more elusive.

So, in times like these carrying the Core out into the world is more important than ever. For the Core has taught you to engage differently, even in the face of the most disagreeable voices and the most intractable-seeming problems. And if you believe, as I do, that the Core is to the University what the University is to society, the greatest application of what you have learned here is still to come. It is about acting as a bulwark against our natural inclination to intolerance, and leading our enduring search for those critical shared truths. It is about projecting the spirit of the Core out into the world, whatever part of the world you make your own. A classroom, a newsroom, or a courtroom. A business or a canvas. A lab or a hospital. A public office or a personal relationship.

In all of these places and so many more, you will have the opportunity in interactions big and small to define that core, and exemplify it for those around you. That you have been part of this effort we have no doubt, nor that you will continue to do your part to see us through to the end.

On behalf of all of us here at Columbia, the Trustees, the administration, the staff, and the faculty, we extend our warmest congratulations and gratitude to you, the Class of 2018.