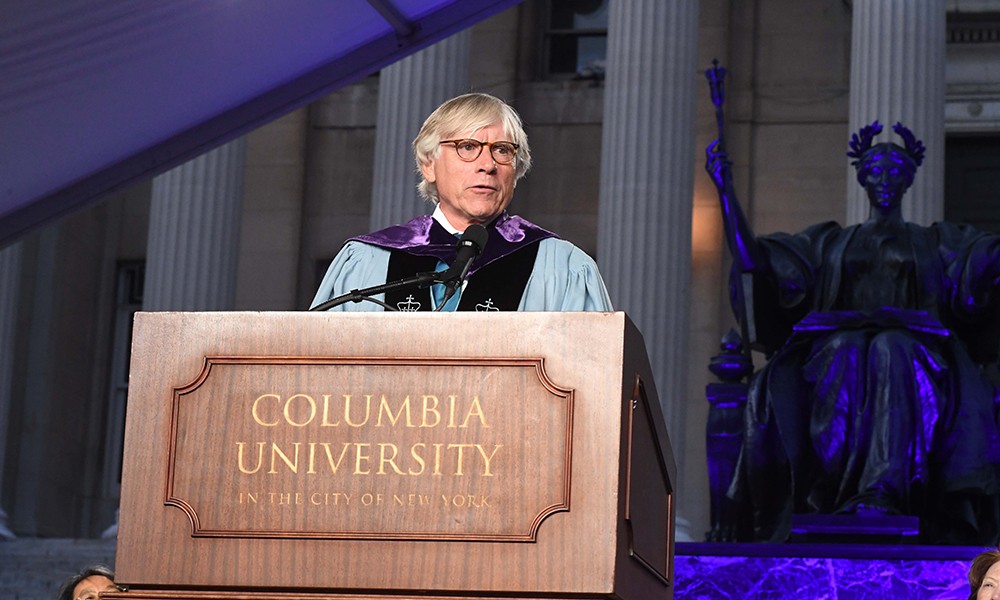

During new student orientation, President Bollinger addressed the students and the families of the Columbia College and Columbia Engineering Classes of 2023.

August 25, 2019

No occasion in the academic calendar is more meaningful, or filled with happiness, than Convocation—the formal welcome we extend to you, the newest members of our community. The beginning of the academic year is always a time characterized by hope and excitement about the possibilities ahead. But what makes it truly special is the renewal of our purpose by your presence. I mean this, and, on behalf of the entire faculty and the institution as a whole, I want to convey to you our enormous pleasure at your joining us. I also want to say, to the parents and families attending this evening’s ceremony, that we appreciate the complex feelings you are experiencing at this moment. Pride, joy, apprehension and anxiety, relief—these emotions are heightened at this time, and, if we’re successful at this Convocation, they will be made even more intense. Thank you all for becoming part of this very, very great institution that we all love and cherish.

I want, in the few moments I have with you tonight, to talk about the fundamentals of Columbia University and of universities generally—what we are about, what we do, what we are committed to and believe in—and to contrast that with distressing trends in the world beyond these academic gates. I want to try to speak you in the moment—your moment, really, for this will be a significant part of the reality in which you will be in college, which is always part of what makes the whole thing such a distinctive life experience. I seek here to offer some context for what will follow after this Convocation, as you settle into the experience of being a student at Columbia.

What is a university? This, of course, is a profound question, beyond the range of a small Convocation talk to answer. But, for our purposes now, here is what I would say. Universities are all about knowledge, about discovering truth, about unraveling the mysteries of life and the natural world we inhabit, about grasping and holding in one’s mind the complexities of existence. A university is not about making money or profits, or exercising power, or creating policies, or worshiping a deity, or being in a club, or having a good time, or building a relationship. These ambitions are often—usually— fine in themselves, and universities are not entirely removed from them, but they do not constitute the essence of a university. Our essence is in the sense of wonder, curiosity, and the steadfast pursuit of understanding things better than we know now. There is always a forward momentum to universities. We most certainly have enormous respect for the past, and we are full-fledged members of that little troupe of explorers who have populated humankind over the millennia, but we are always in the moment and moving forward with the strong currents of curiosity.

So, this is what we are at base. But there are three important additional points to be made here. One is to recognize that this spirit of inquiry is not the result of some independent right or privilege we happen to possess. While we are a “private” university, we are still a publicly chartered institution, which gives rise to profound responsibilities to our societies and to the world. In that sense, there is very little difference between “public” and “private” universities in America, and altogether the spirit of serving the public good by advancing knowledge over time has resulted in the greatest system of higher education and research universities in the world, with incalculable benefits to humanity. I assure you, we are all fully conscious of our public mission.

"Our essence is in the sense of wonder, curiosity, and the steadfast pursuit of understanding things better than we know now."

The second point to be made here is the pursuit of truth in universities takes place within a framework of norms and principles that are rigorously enforced and zealously guarded. In universities, you must adhere to facts, commit your ideas to logic and reason, give appropriate acknowledgement to the ideas and contributions of others, recognize counter-arguments and perspectives, demonstrate open-mindedness and a capacity for self-criticism, and conduct yourself with civility and respect for others—especially those with whom you disagree. We know we are extreme in these conditions—any act of brazen falsification or falsehoods or of taking the ideas of others as your own suffers the academic capital punishment of banishment from the scholarly profession. To be a scholar you must situate yourself in these norms.

And now the third point about universities—which may seem inconsistent with what I have just said about the norms of a scholarly temperament, but is not, in fact. Universities are also living communities, civic communities, and, as such, we have in addition to research and teaching what in essence amounts to a public forum, where faculty and students can discuss and debate the issues of the day. In this realm, we abide by the constitutional principle of freedom of speech—and that means that virtually anything can be said about any public issue (with some exceptions I won’t go into here). No one outside this University has a right to come onto the campus and speak, but, as part of their free speech rights, faculty and students may invite outside speakers from time to time. And in this limited public forum, within the University, we have chosen to follow the nation and to protect all viewpoints on public issues, no matter how offensive or dangerous they may be. This is, to be sure, a reasonably debatable choice, but it is our choice and therefore a reality of life that we must all learn to live by—one in which there will be “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open” debate, where we must rely on our own voices to reject ideas we deplore rather than shrink from that world into censorship. Challenge that reality if you wish, but do not expect the institution to protect you from it while it stands. Columbia, in particular, has a long and proud tradition of protecting and engaging with difficult speech.

So, this is what a university is. It may sound banal, but it is accurate nonetheless. It is by design, by principle, different from the outside world, to some extent—not separate from it, but different.

There are, of course, and it’s worthy to note, criticisms of our institutions. Universities, it is sometimes said, are too ideological, too left-leaning, lazy, out of touch with the real problems of society, too rich, too expensive, too suppressive of free speech, and so on. I have written and spoken about each of these critiques on many occasions. I cannot say more about them today. But I do want to acknowledge them, and I do want to say that we are ourselves highly self-critical and always trying to be better at what we do. We understand that we need to take a more global perspective on the world, for example, from the standpoint of our scholarship and teaching. We now have nine Columbia Global Centers spread around the world ready to assist our faculty and students in that effort. We understand that universities should be more active and systematic in making research and knowledge generated here available to those who can use it to benefit humanity. A new initiative called Columbia World Projects is experimenting with how to accomplish this goal, and we will this year be looking deeper into the institution to see what can be done more broadly. We sometimes call this the fourth purpose of a university, how to bring academic knowledge to work in the world, in addition to our mission of research, education, and public service. We will this year also focus specifically on what more we can do to mobilize the resources of the University to focus on consequences of climate change. So, there are criticisms—some are fair, some not—and, in the spirit of academic inquiry, we are always open to criticisms and intent on improving.

"Every time you enter a Core Curriculum class, or any class, or feel the exhilaration of learning and thinking something new, or engage in the campus debates on the pressing issues of our time, I hope a part of your mind will remind you of these deeper principles at work and of where they came from."

Now, I want to shift from the university to the world beyond the university, briefly. I want to take note of a very dangerous phenomenon that has arisen here and across the world in the last several years. The problem we have today is that there are trends in the outside world, especially the political world, that increasingly reject the fundamental principles on which the very special qualities of universities have been established. It is a hard fact of contemporary life that there is a declining respect for truth, reason, knowledge, civility and decency, and human rights. Universities must refrain from taking sides on political issues, so I am not here speaking about the fierce debates now occurring on trade policies, immigration, or abortion, and so on. What I am speaking about is the lessening regard for what we broadly call the search for, and respect for, truth and for the intellectual framework and character needed for that search to fruitfully happen. When anything can be said and believed, the conditions of democracy are lost, and when democracy is lost, a university cannot survive. It has no meaning. We, of course, are not there yet, but the trend is there, and it is the defining fact of our—most importantly, your—time—so much so that I think it cannot go unmentioned even on an occasion as celebratory as this.

All this said, this is not by any means a time for despair. I think this is demonstrated for us by three interconnected events that occurred in times of similar stresses 100 years ago exactly. The descent into chaos and destruction that was World War I, the ideological conflicts around the political systems that created such upheavals in nations, and the intolerance and injustices inflicted on dissenters, minorities, immigrants, and vulnerable populations defined the era in which people who still believed in the validity of Enlightenment values stepped in to repair the breaches. They are role models for us today. Of immediate interest to you is the creation of the Core Curriculum, as mentioned, the singular and defining feature of a Columbia education. Whatever one believes should be included or excluded from the Core, which is, very properly, an ever-ongoing debate, the very idea of a core, of being immersed in a body of knowledge and thought, of being exposed to the works of many of the greatest minds engaged in the quest for truth, not in some pre-digested form delivered through the medium of the lecture, but to be lived with and to be debated and discussed with your peers, the efforts to probe the most profound questions of life—this was a reaffirmation, a doubling down, of the values of knowledge, at a moment when the world seemed to be coming apart at the seams.

Similarly, in 1919, this was precisely the moment when the United States Supreme Court began its modern interpretation of the principles of freedom of speech and press, which over the course of the last century that followed has made this country the most protective of thought and speech and press in history. This, too, was premised on the same idea that truth is the goal of life and society, and that demands an intellectual character composed of extraordinary tolerance and a capacity for self-doubt. This was, as it were, the First Amendment’s Core Curriculum for America.

And, finally, in a more generalized sense, approximately one hundred years ago was the beginning of the modern research university and all the values I summarized at the outset. And today, Columbia, stands at the very top of those institutions.

Then, as now, out of the potential unraveling of the values of knowledge, reason, and truth, people and institutions stepped forward to renew the values.

I say all of this for several reasons. It is always valuable to restate the philosophical underpinnings of what one is doing. So, as you begin here, that’s good for you to know. But it is especially valuable and important today because of contrary trends that threaten to undermine those bedrock principles. And, finally, it is good in these moments to appreciate the elements of our daily lives that reflect the efforts of those who came before us to sustain and build up that foundation, to realize that the foundation is fragile but enduring, and to never take what we have for granted. Every time you enter a Core Curriculum class, or any class, or feel the exhilaration of learning and thinking something new, or engage in the campus debates on the pressing issues of our time, I hope a part of your mind will remind you of these deeper principles at work and of where they came from.

Good luck and welcome to Columbia.